- What is Toughness?

In mechanical design and materials engineering, materials must not only possess sufficient strength under load but also be capable of absorbing a certain amount of energy before failure to avoid sudden, catastrophic fracture. This ability of a material to absorb energy prior to fracture is known as toughness. Toughness is a crucial indicator of a material’s overall mechanical performance, closely related to its strength, ductility, microstructure, and defect state.

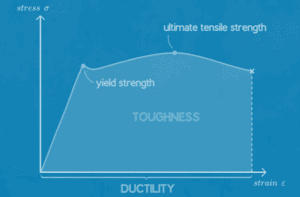

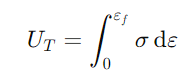

From a mechanics perspective, toughness refers to the deformation energy absorbed per unit volume before fracture, typically represented by the modulus of toughness, UT. Numerically, it equals the area under the stress-strain curve from zero strain to the fracture strain.

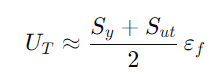

In engineering calculations, toughness is seldom determined by precise integration. Instead, an approximate method is often used: the average of the yield strength (Sy) and ultimate tensile strength (Sut) multiplied by the fracture strain (εf).

This shows that toughness depends on both strength and ductility. Generally, ductile materials, due to their large fracture strain, exhibit significantly higher toughness than brittle materials. For example, a car’s metal body can absorb substantial energy through plastic deformation during a collision, whereas brittle materials (like some composites or glass) cannot absorb sufficient energy and tend to fail suddenly.

- Impact Testing and Impact Toughness

In practice, many components operate under impact loading rather than static conditions—examples include automotive braking, sudden velocity changes, and equipment like forging hammers, punch presses, and crushers. A material’s ability to resist damage under impact loads is called impact toughness.

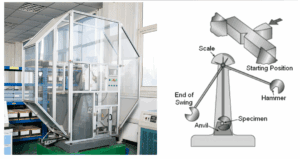

Impact toughness is typically measured using a pendulum impact test, such as the Izod or Charpy test. A pendulum hammer, released from a specified height, strikes and breaks a standardized notched specimen. The energy consumed in fracturing the specimen is calculated from the difference in the pendulum’s height before and after impact. Dividing this energy by the original cross-sectional area at the notch gives the impact toughness index, aK.

While impact testing does not directly provide the energy area under a stress-strain curve, it offers a straightforward and effective method for comparing the energy absorption capacity of different materials. Impact toughness is highly sensitive to microstructural defects, manufacturing quality, and heat treatment conditions, making impact tests a vital tool for material quality inspection.

- Ductile-to-Brittle Transition and Engineering Safety

Many steels undergo a significant change in impact toughness with temperature, transitioning from ductile to brittle fracture. This phenomenon is known as the ductile-to-brittle transition, and the critical temperature is called the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT).

Generally:

Low-carbon and low-strength steels have a relatively low and distinct DBTT.

High-carbon and high-strength steels often lack a clear transition range, requiring a specified impact energy level as an evaluation criterion.

A lower DBTT indicates safer material performance in low-temperature environments. Historically, numerous brittle fracture failures in ships, bridges, and pressure vessels under cold conditions have been linked to overlooking this transition behavior. Therefore, codes and standards for large structures and components serving in low temperatures typically specify minimum service temperatures and minimum impact toughness requirements for steels.

- Repeated Impact and Material Selection

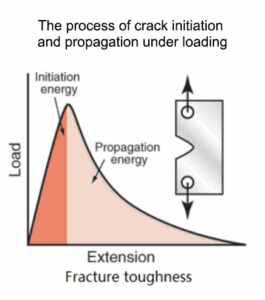

In engineering applications, components more frequently endure repeated, low-energy impact loads rather than single high-energy blows. Under such conditions, failure results from the gradual initiation and propagation of cracks due to repeated impacts, which is fundamentally different from a single high-energy event.

Research indicates that material ductility dominates resistance under high-energy impacts, whereas under low-energy, repeated impacts, material strength often becomes the primary factor determining service life. Therefore, material selection should not solely pursue high impact toughness but should balance strength, ductility, and toughness according to the specific loading conditions. For instance, certain malleable cast irons with moderate impact toughness can be successfully used for manufacturing crankshafts in internal combustion engines.

- Fracture Toughness and Crack Control

With the widespread use of high-strength steels and large welded structures, engineering experience has shown that sudden brittle fractures can occur even when working stresses are far below the yield strength. Studies reveal that such failures are almost always associated with the propagation of pre-existing cracks within the material or on its surface.

With the widespread use of high-strength steels and large welded structures, engineering experience has shown that sudden brittle fractures can occur even when working stresses are far below the yield strength. Studies reveal that such failures are almost always associated with the propagation of pre-existing cracks within the material or on its surface.

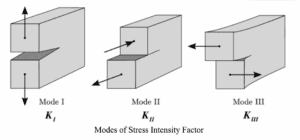

Fracture toughness is a mechanical parameter that characterizes a material’s resistance to unstable crack propagation, usually denoted by the critical stress intensity factor, KIc. It is a key indicator in materials science, reflecting the material’s ability to resist crack growth. When the stress intensity factor KI at the crack tip reaches KIc, the crack undergoes unstable propagation, leading to component fracture. A higher KIc indicates greater resistance to brittle fracture.

intensity factor, KIc. It is a key indicator in materials science, reflecting the material’s ability to resist crack growth. When the stress intensity factor KI at the crack tip reaches KIc, the crack undergoes unstable propagation, leading to component fracture. A higher KIc indicates greater resistance to brittle fracture.

Fracture toughness is closely related to material composition, microstructure, and manufacturing quality, and is significantly influenced by non-metallic inclusions. Therefore, for high-strength steels requiring high fracture toughness, strict control over melting and processing quality is essential, supplemented by non-destructive testing to limit flaw sizes.

Fracture toughness is closely related to material composition, microstructure, and manufacturing quality, and is significantly influenced by non-metallic inclusions. Therefore, for high-strength steels requiring high fracture toughness, strict control over melting and processing quality is essential, supplemented by non-destructive testing to limit flaw sizes.

- Summary

In conclusion, toughness is not a single property but a comprehensive set of characteristics encompassing static toughness, impact toughness, and fracture toughness. In engineering design, relying solely on strength criteria is insufficient to ensure safety.

At EMP, we translate this understanding of material toughness into rigorous engineering practice. For every component, we undertake stringent material selection based on specific client performance requirements and operational environments. This is followed by the prudent application of material toughness principles in our design and manufacturing processes. Prior to delivery, products undergo necessary performance and qualification testing, including but not limited to impact toughness and fracture mechanics evaluations as warranted. This comprehensive approach is integral to our mission of preventing sudden fracture incidents and ensuring the long-term, safe operation of engineering structures.